As he turns a magnificent 90, Mr Armani celebrates some of his most major moments in Vogue with Robin Muir

Milan, summer 1975. A 41-year-old Giorgio Armani has sold his blue Volkswagen Beetle to finance a new fashion business. He rents a tiny office and hires two members of staff: a young secretarial student, Irene Pantone, and an irrepressible showman from Tuscany, Sergio Galeotti, who is in charge of sales. In what passed back then for a showroom, the three brought out a menswear collection, followed by one for women. Both debuted to great acclaim, the buying public entranced by the deceptive simplicity and elegance of Armani’s clothes. In time, a new glossary would be coined for his palette: “greige”, “sand”, “mushroom”, “biscuit”. American critic Dodie Kazanjian would write in Vogue that Armani was “doing for the jacket what others were doing for philosophy, architecture and art”.

Advertisement

“I have always looked forward and sought to act in the present,” Mr Armani tells Vogue, almost 50 years later, ahead of his 90th birthday in July. Still in command half a century on, still the head of a now billion-dollar empire (at a recent reliable count he had some 9,257 employees and 2,294 stores in 80 countries), the designer is not and has “never been nostalgic”.

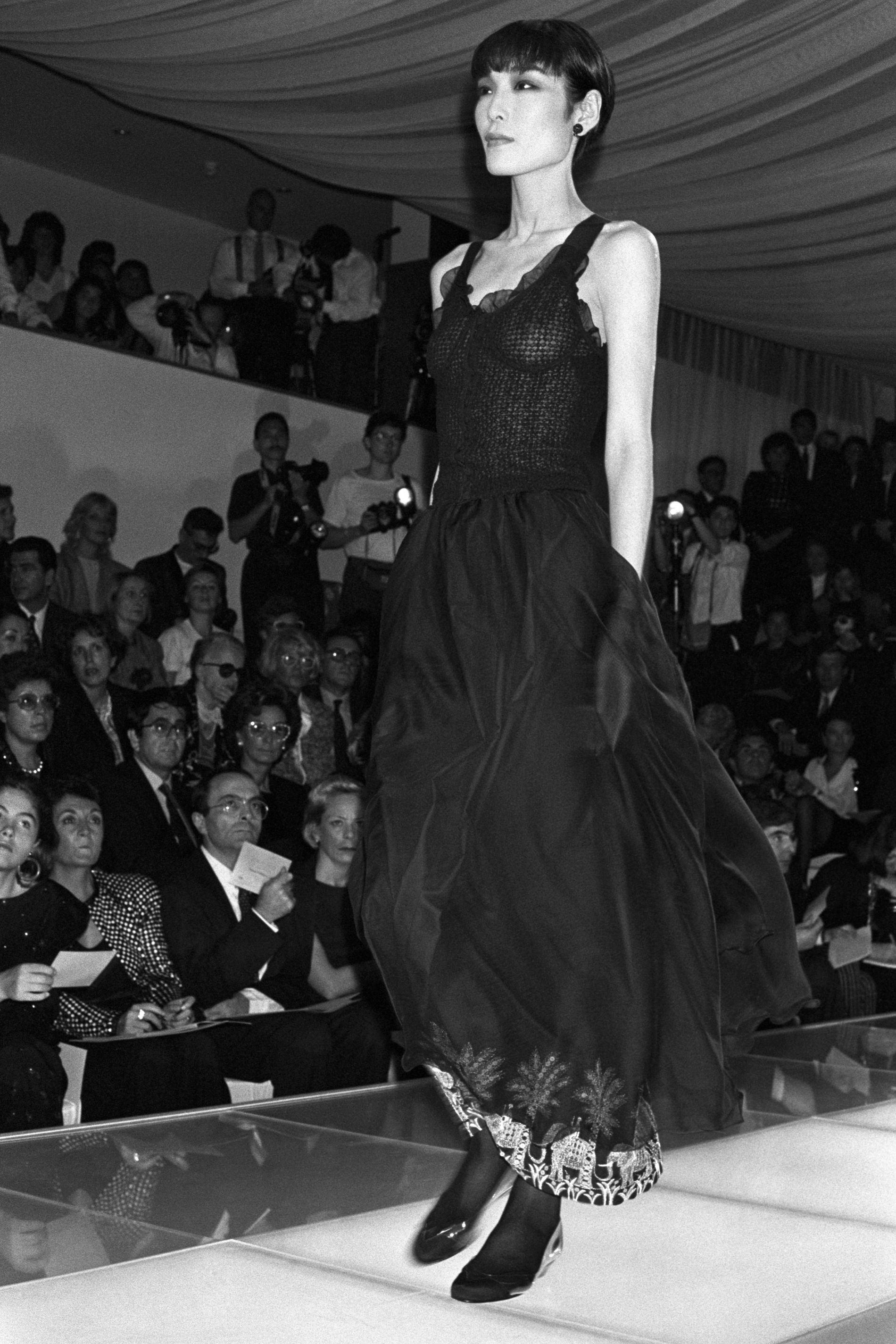

Armani's spring/summer '87 collection, presented in Milan. Photo: Fairchild Archive / Getty Images

His idea of style was defined at the beginning and has remained unchanged. “I believe in consistency, which does not mean rigidity, but adherence to certain principles,” he says. “My ultimate goal is to create clothes that celebrate the individual, almost disappearing when worn to allow the wearer’s personality to emerge first.”

My ultimate goal is to create clothes that celebrate the individual, almost disappearing when worn to allow the wearer’s personality to emerge first.

Giorgio Armani

Indeed, by his own measure, the Armani look has only evolved by “millimetric margins”. Take the power suiting he was creating in the 1980s, for instance, or the red two-piece worn by Jade Parfitt in the late ’90s, then Jourdan Dunn in 2011, in an impeccably tailored jacket and trousers. There are differences, yes, though they are, as the designer says, millimetric. Their provenance is unequivocal.

How did he feel about Corinne Day’s picture of Sarah Murray, supermarket checkout girl turned model, representing an anti-fashion moment in Vogue in 1993? Did this portrayal of an Emporio Armani jacket confound him?“On the contrary, it pleases and excites me,” he says. “I do not believe in class distinctions in fashion: fashion is truly for everyone, regardless of spending power. This is an image of style: natural and personal.” That is, he adds, “exactly how I like it”.

Danish supermodel Helena Christensen walks Armani's spring/summer '94 show. Photo: Penske Media / Getty Images

Like many who grew up in the shadow of war, it was cinema that offered the young Armani an escape: Italian neorealism, then the glimmering technicolour of Hollywood. With a foresightedness all but then unique in his world, he began to dress the stars themselves in public and, enduringly, on the red carpet. In 1978, Diane Keaton accepted her best actress Oscar for Annie Hall in a neutral-coloured, deconstructed Armani jacket in crumpled linen and a layered skirt. By 1990, so ubiquitous was the label on the red carpet that the Oscars was nicknamed The Armani Awards.

“What happened with my fashion and Hollywood was an extremely fruitful and advantageous two-way exchange,” he explains. “It was mainly the new stars, lightyears away from the Golden Age personalities, who engaged with my very personal and natural vision of fashion.” Still his eveningwear – sweeping dresses with plunging necklines or the classic structured strapless columns beloved by Cate Blanchett and Zendaya – dominate awards season.

Perhaps that is because Armani knows exactly how to do glamour without being ostentatious. Though sometimes, quite often actually, he surprises with vibrant bursts of colour and unexpected exercises in experimentation. Take Kate Moss on the December 2001 cover of British Vogue, in tomato red tulle. “I really like to push my limits,” he admits, but – naturally enough – “my approach is careful and considered. I call myself an eccentric to a certain extent and varying degrees of exuberance can be found in all my work.”

Mr. Armani takes his bow after the Giorgio Armani Privé Haute Couture fall/winter '25 show. Photo: Mark Piasecki / Getty Images

The mercurial Sergio Galeotti died young, in 1985 on the 10th anniversary of a company he had, it turned out, been very good at managing. “Whatever I did in work was done for Sergio,” Armani once said, “and Sergio did everything for me. So that was the heart.” Meanwhile, Irene Pantone, the secretarial student from long ago, only retired in the last few years, having been with Armani her entire working life.

And what of the man himself? He is, at 90, effectively the sole shareholder, holding the company’s independence in a famously tight grip. “The future of the Armani Group will be decided and governed by the Foundation,” he says of the governing body of close associates he set up in 2016. In the end, perhaps, it’s all about celebration. “To me style is not about being noticed,” Armani concludes, “it’s about being remembered.”

Originally published on Vogue.uk.