In fulfilling director Robert Eggers’s wish that every last detail of The Northman has to be as thoroughly researched as possible, costume designer Linda Muir had to visualise a world whose presence in popular culture bears little resemblance to the historical reality. Here's how she did it

When it comes to costuming a period epic, there are plenty of resources a designer seeking to achieve the utmost historical accuracy can turn to: museum pieces, fashion plates, archives, even extant scraps of textile. But when it came to working with the auteur Robert Eggers on his new Viking epic, The Northman—a jaw-dropping, go-for-broke tale of savagery and spirituality starring Alexander Skarsgård, Anya Taylor-Joy, Nicole Kidman, and Björk as an Eastern European seeress—costume designer Linda Muir was faced with an entirely new set of challenges. In fulfilling Eggers’s wish that every last detail be as thoroughly researched as possible, Muir had to visualise a world whose presence in popular culture bears little resemblance to the historical reality.

“It was the biggest project I’ve ever done, the biggest team I’ve ever worked with, and the best experience of my career,” says Muir, who previously collaborated with Eggers on his critically acclaimed breakout films, The Witch and The Lighthouse. “Just the biggest in every way.” It’s clear that Muir found Eggers’s approach as exciting and galvanising as she did (very understandably) a little intimidating. “Robert is quite unique in that he really grounds himself and his writing in the facts—he loves research, he loves reading, he loves history, he’s very passionate about it,” says Muir. “So we as the creative teams started with a huge amount of information, which was a beautiful gift.”

The first challenge was simply the fact that scant evidence of what the Vikings—who emerged from Scandinavia in the early medieval period before conquering vast swathes of Europe throughout the so-called Dark Ages—actually wore survives. Sure, there are scraps of wools, leathers, and furs from the period that you can find in museums today and a much wider offering of hardier pieces like jewellery and armor, but to understand what the day-to-day citizen or warrior or, indeed, woman might have worn, Muir had to dig a little deeper. “We had the help of some brilliant historians and consultants, but it involved a vast amount of research,” she says.

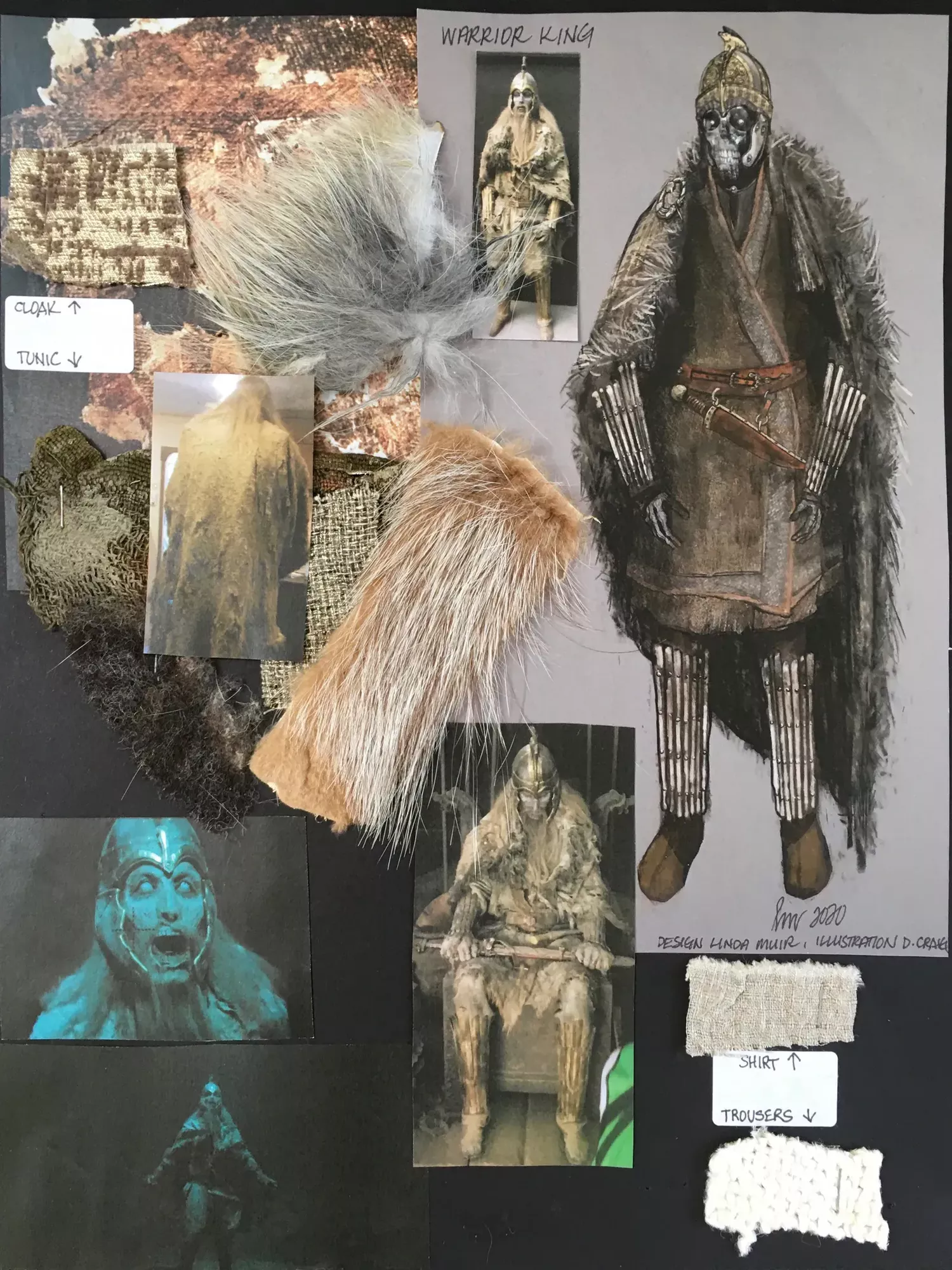

Costume sketches for the Warrior King. Photo: Courtesy of Linda Muir

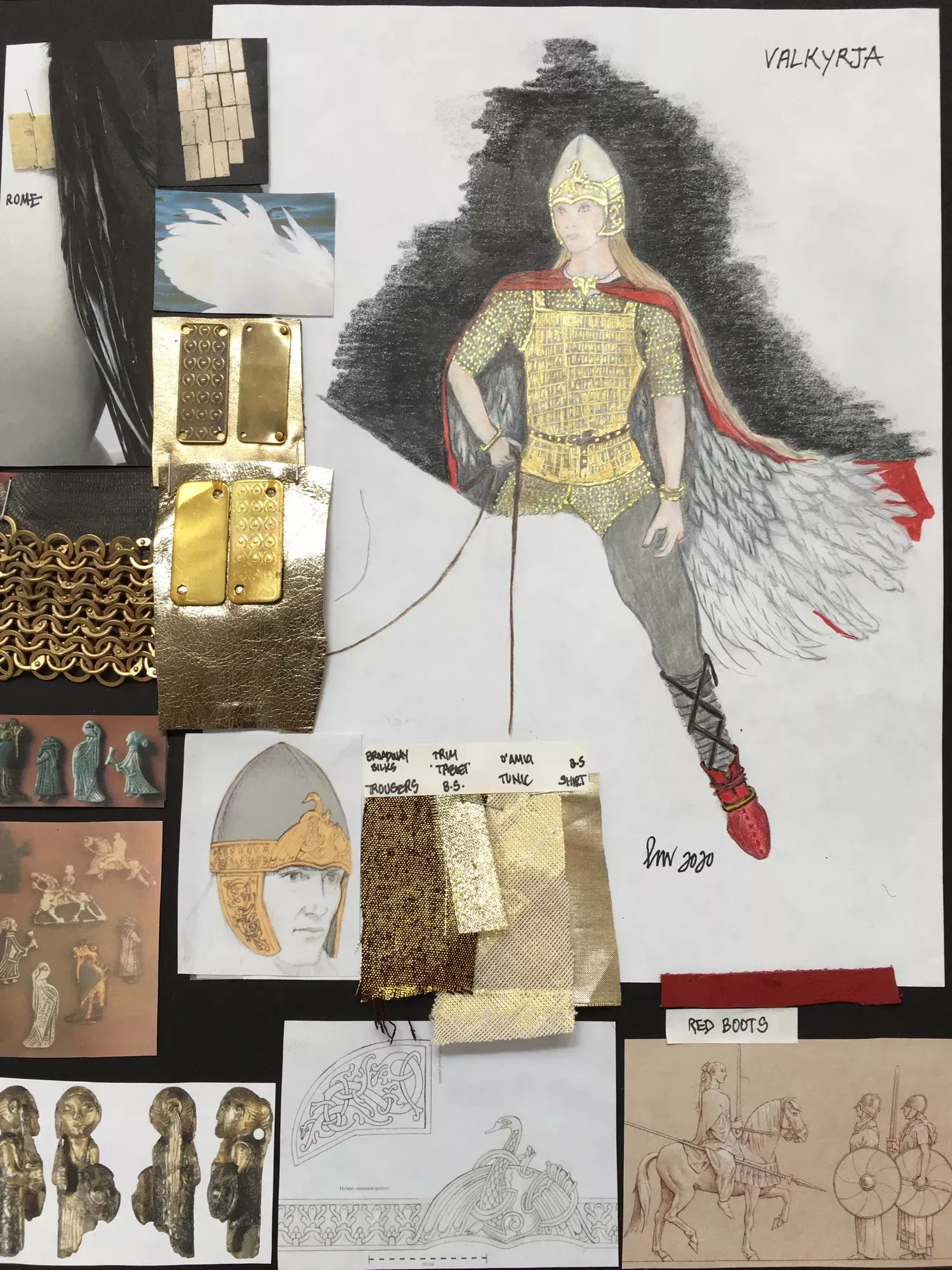

Costume sketches for the Valkyrie. Photo: Courtesy of Linda Muir

Additional costume sketches for the Valkyrie. Photo: Courtesy of Linda Muir

Then there was the sheer array of figures for which Muir had to devise a sartorial language: both the mythic and the very much real—encompassing communities from one end of Europe to the other—and at specific moments in Viking history over the course of the film. There are Valkyries and witches, kings and queens and princes, jesters and warriors, nobles and savages. They might hail from modern Iceland or a mysterious island somewhere in the North Sea or the furthest reaches of the Viking empire during its greatest period of dominance in the 10th century: namely, the Rus’ states, which span regions of what is now Belarus and Ukraine.

What lends the film its unique magic, however, is not just its ability to spin a ripping yarn informed by Viking mythology but also its focus on aspects of the culture that have been historically underrepresented. For one thing, it wasn’t just men fighting on the battlefields or achieving positions of supreme status. (Within The Northman, after all, it’s the female characters that propel the narrative forward, from Björk’s mysterious Slavic seeress to Anya Taylor-Joy’s enslaved witch Olga and Nicole Kidman’s fearsome turn as Queen Gudrún.)

For this, Muir also had to think outside of the box, given the emphasis in historical accounts on the traditionally masculinist elements of their society. “I was talking to [archaeologist and historical consultant on The Northman] Neil Price about Viking women when designing Nicole’s costumes, and I asked, for instance, ‘What do you think might have made a Viking woman feel sexy?’” Muir recalls. “And he kind of laughed and said, ‘No one has ever asked me that before.’” To bring the Viking world to vivid, full-fleshed life, however, it’s exactly the kind of question the job required. Here, Muir tells Vogue about the difficulties—and the unexpected delights—of her extraordinary work on The Northman.

Oscar Novak stars as Young Amleth. Photo: Photo: Aidan Monaghan / Courtesy of Focus Features

Nicole Kidman as Queen Gudrún. Photo: Photo: Aidan Monaghan / Courtesy of Focus Features

Vogue: You had worked with Robert on both The Witch and The Lighthouse. When you first started having conversations about The Northman, what was it about the project that excited you?

Linda Muir: Well, first of all, it’s just a fantastic script. It’s not just an epic—the characters that Robert and Sjón [Eggers’s cowriter] have created are incredibly well developed. They have motives, ulterior motives; they have what you see on the surface and then something much deeper beneath that. Initially, I didn’t really know all that much about the Vikings in terms of facts and figures—it wasn’t an area that I had really explored before, so that was exciting in and of itself. It was so fascinating to research, but the overriding desire was just to work with Robert again because it’s always such a joy.

The attention to historical detail is mind-blowing. How much of the research did you do independently, and how much of it was a case of you pooling your reading and resources with Robert and Craig Lathrop, the film’s production designer?

It was a combination of both. This is the third time the three of us have worked together, so we knew when we needed to come together. I did all of my very early, pre-prep research online—sending out emails into the ether, hoping for answers, trying to find people who would have pertinent information—partly because of COVID. For me, the initial work was really finding the people to work with in Belfast and then bringing them on board with the notion that this will be a very different visual idea of what Vikings have looked like on film previously. I went to rental houses and on a huge scouting trip for fabrics—I went to London, Rome, Prato, Madrid. Although it was very fruitful in terms of textiles, it became clear pretty quickly that there wasn’t much other than boots and shoes for the crowd, and maybe some helmets and chain mail, that we would be able to rent. So when I returned, we started having those discussions about the fact that we were going to have to make pretty much everything that you see on the screen. And that is a huge undertaking, particularly when you take into consideration the number of multiples for any of the given garments—for rider doubles, stunt doubles, photo doubles—and that became even more complicated with COVID. People couldn’t come and go with the same ease, so a lot of garments would have to be ready much earlier, or they would arrive at the last possible moment for shooting. In terms of fitting and finishing all of these hand-sewn pieces, the schedule became quite tight.

Willem Dafoe as Heimir the Fool. Photo: Aidan Monaghan / Courtesy of Focus Features

Within that research process, were there any unexpected sources that proved to be especially fruitful?

Along with reading the sagas, I came across a book by a woman called Nille Glæsel, who is Danish but lives in Norway now. And she’s been making Viking clothing for over 20 years. She is a living archaeologist—a contemporary Viking woman. And so I had some questions about very specific designs that I wanted to include, particularly for Queen Gudrún’s costuming. And from Nille’s book, I had gleaned this idea that pleated shifts would go under all her clothing and be used as nightwear. Nille and I started up a conversation via email, and she was terrifically helpful. So I thought, Maybe I’ll ask Nille to come and join us. She doesn’t have film experience, but she certainly has Viking experience. And that was, in hindsight, a really crucial decision because she was just a font of information about these very specific construction techniques. I would look at pieces from museums or things that archaeologists had written, but then to translate that into actually constructing these pieces was a whole other task.

Once you had settled on the fabrics and techniques that felt authentic to the period, how did you then set about translating that into the thousands of costumes we see on screen?

We had an incredible team, I think over 80 makers. There is an extraordinary amount of hand-sewing and hand-embroidery in the film, so we had our work cut out for us. A lot of the textiles I had found to use were one-offs; they were plant-dyed pieces and beautifully handwoven wools. At one point, I was joking that I was afraid I was going to kill our Polish weaver—he was 80 years old, and I just kept asking for more and more of his beautiful wool. [Laughs.] But they had to precut the pieces into a certain dimension in order to plant dye them effectively—so for our purposes, where we might need three of the same garment, I had to figure out different ways of extending the fabric to make all the garments we needed.

But in the end, that was actually a very Viking approach—they were incredibly economical. I mean, there really isn’t one complete garment, certainly not a complete outfit, that is available to inspect from that time. But archaeologists and Viking clothing historians have gleaned a certain amount of information from what has been found and their depictions in stories or artwork. The question is really: How do you interpret the way in which these garments were actually made? That was the largest part of the work.

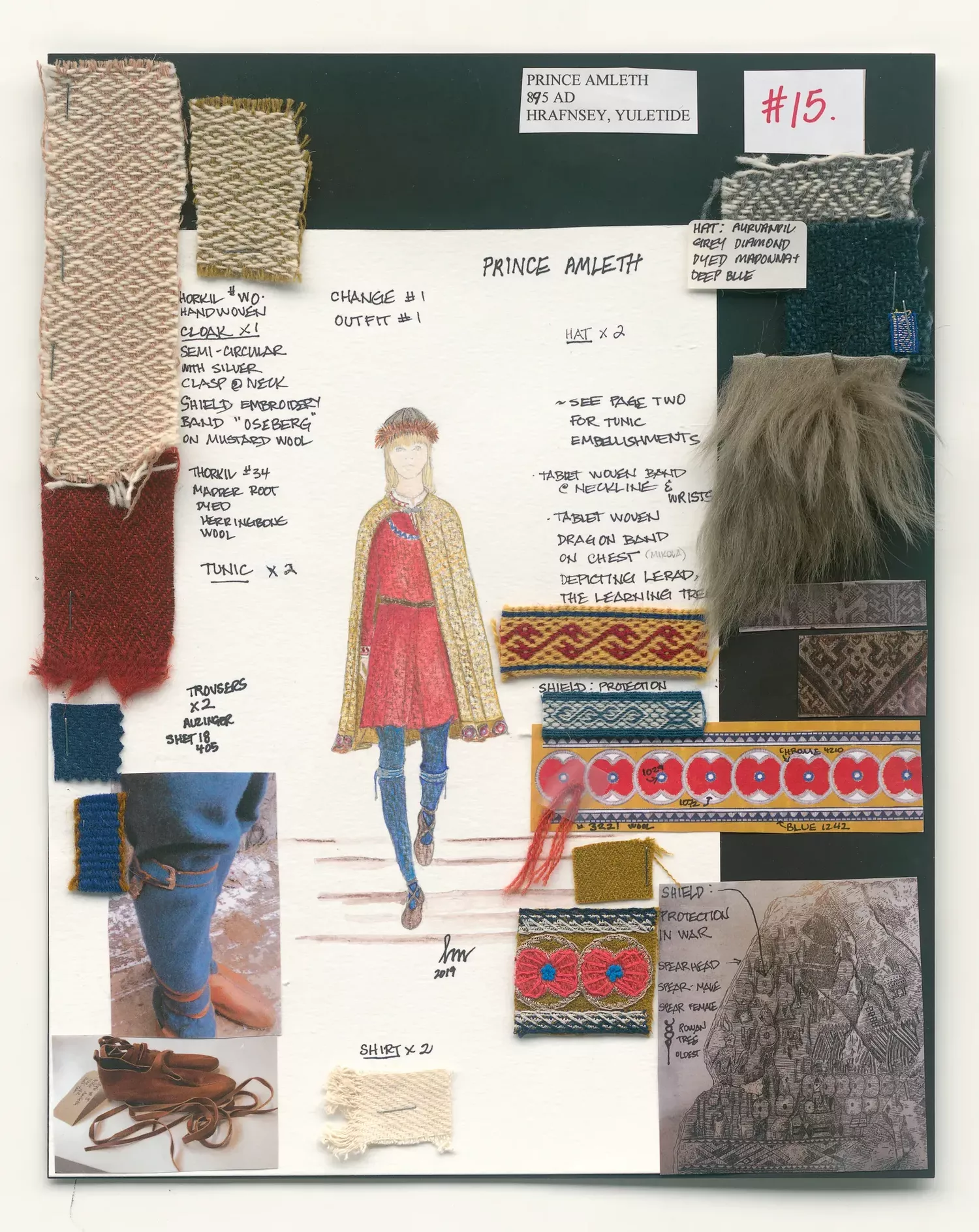

Costume sketches for Young Amleth. Photo: Courtesy of Linda Muir

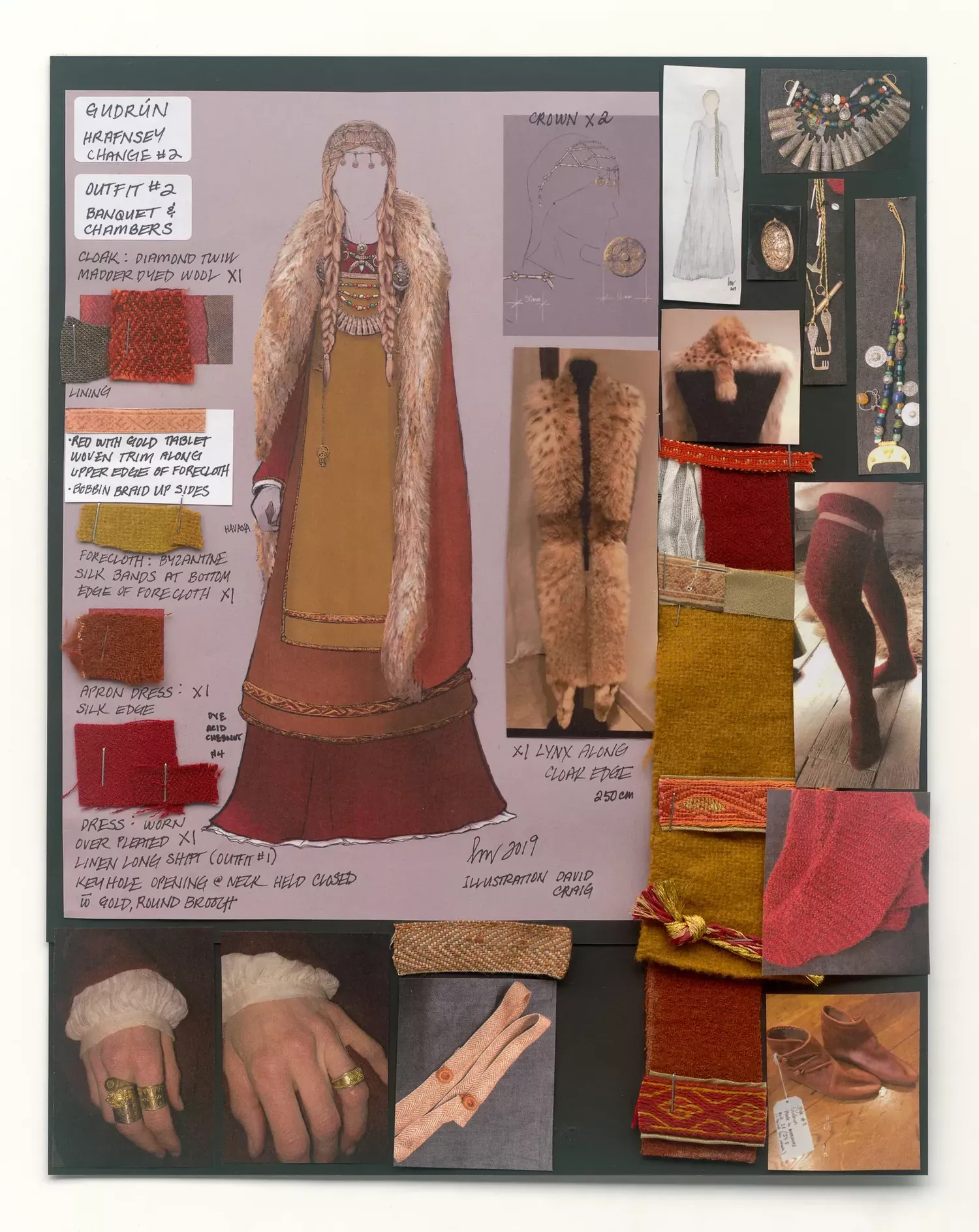

Costume sketches for Queen Gudrún. Photo: Courtesy of Linda Muir

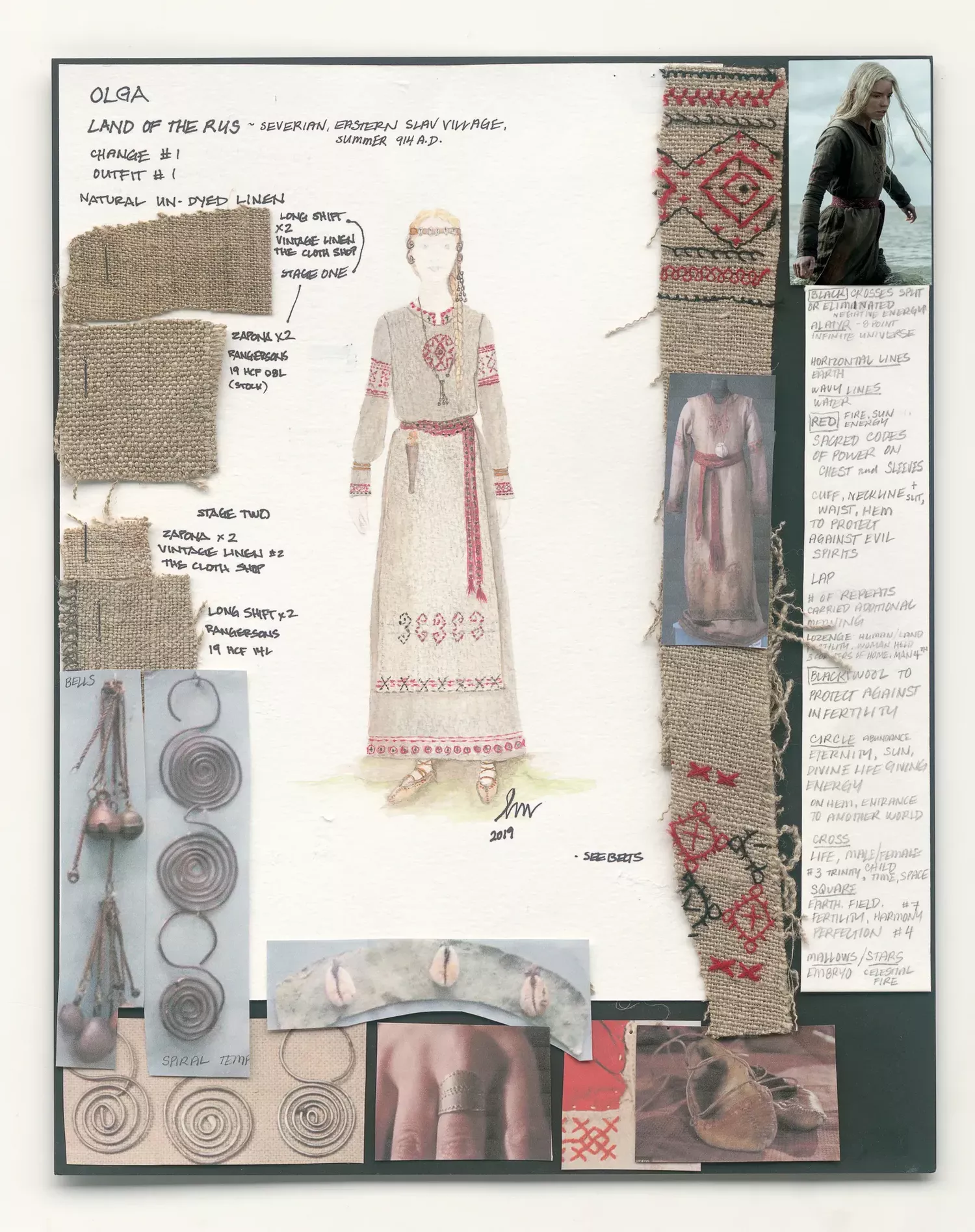

Costume sketches for Olga. Photo: Courtesy of Linda Muir

When it came to filling in the gaps of what we don’t really know about certain categories of Viking clothing, how much freedom did you allow yourself?

I used the information that was available to form the baseline, and then I tried to channel a Viking sensibility, I suppose. The ceremonial wear is probably the largest area of creation because we know bits and pieces about how the deceased were clothed or what they were surrounded with in the burial mounds, but we don’t really know how the people grieving those loved ones dressed. We do know that there was a lot of blood sacrifice. I also felt very strongly that textiles must have been a huge part of Viking commerce and a commodity and must have been a valuable part of their lives. It would have taken so long to create these textiles, so I couldn’t really see them being disposable.

We also had conversations with Neil Price, who was absolutely amazing at helping fill in these gaps of information with supposition and theory and practical advice. Robert and I spoke to him about ceremonial wear, and I told him that in my research I had gleaned that white wool must have been special because white sheep were rarer, and so I didn’t believe that they would get rid of that clothing. But clearly they weren’t walking around crusted in stinky, dirty blood—that wouldn’t have been a good idea in terms of hygiene or anything else, really. So practically speaking, they must have washed these items, but by that point the blood wouldn’t have come out. So it occurred to me that these wool clothes would be left with stains that would show past sacrifices, past events, past funerals. The clothing would become a sort of canvas of the history of these people, so we ended up staining the multiples to appear the same. Whether that reads on camera or not, I’m not sure, but that was the notion. That’s just one example, but it’s to say that there was invention, yes, but we were still hopefully using the real information that bubbled up all over the place from the research.

There are plenty of standout costumes, but one of the most striking—and one of my personal favourites—is Björk’s costume as the seeress. What was the story there? Was Björk involved in the development of the outfit at all?

It mostly came from research Robert had done, apart from the addition of the pieces hanging in front of the eyes. Björk felt very strongly that because her character’s eyes had been taken by a Viking militia, she should have the cowrie shells for fertility and the bells to ward off evil spirits. Of course, there are the incredible, beautiful headdresses she uses in her own work, that she makes with James Merry, so I think there was a link there with her performance in that one area. But the design equally came from the research we did into Slavic cultures. Obviously, there was the Viking research, but the Slavic research was equally massive. In that period, there were many, many tribes and each had its own culture. I realised quite early on that we had to be very specific about exactly where we were placing this village within that landmass and that it had to correspond to what Craig was doing in the set design, the way the village was constructed, and the carvings and the language used there.

I found a fantastic video from a Russian museum, which one of our producers translated for me, and I learned that during the period the word for embroidery was apparently the same as the word for writing. And then another light went off for me, that it’s being used as a call to the gods—in this case, the Slavic gods, not the Viking gods; they are embroidering their desires for their family. [Björk’s] incredible headdress is based on styles that you would see for Ukrainian celebrations—we opted for barley because if I remember correctly, wheat wasn’t a local crop. She also has a whole lot of necklaces, and I remember the night before we were shooting, Robert called down and said, “Could we add chicken feet to one of the necklaces?” And so I said, “Okay, let me see what I can do.” I called Craig, and he had some latex chicken feet they had made for props, so I sat at my desk and quickly made that up the night before shooting. It’s all in moonlight, so perhaps you don’t see the same degree of detail, but I believe that you can feel it, and Björk brings it to life beautifully. It was very magical to be on set that night, filming that scene.

Björk as the Seeress. Photo: Aidan Monaghan / Courtesy of Focus Features

One of the most interesting aspects of the film is how it looks just as much at the lives of Viking women as at the men. Was there any kind of disparity in the resources available to you when designing the costumes for the male and female characters? And was there anything specific you wanted to express about the lives of Viking women through their clothes?

One of the things that I admire and love about Robert’s writing is his ability to put forward a female perspective. His writing is feminist, even if that’s sometimes secondary or even unintentional. With The Northman, there were a few things that were very important to me when it came to the female characters. You have the shieldmaiden, who you see riding in during the raid, for example. She is loosely based on a grave finding known as BJ 581. While we were shooting, actually, conclusive DNA evidence emerged that the body in this grave, which had been supposed to be female, was certified as female, so that was really cool. And the Valkyrie was also very important to me after reading the sagas. There are examples of women who were very fierce. The Norns [female deities from Norse mythology] are not to be crossed. [Laughs.] So I really encouraged Robert to go for it for the Valkyrie, for example.

Alexander Skarsgård as Amleth and Anya Taylor-Joy as Olga. Photo: Aidan Monaghan / Courtesy of Focus Features

Alexander Skarsgård as Amleth. Photo: Aidan Monaghan / Courtesy of Focus Features

So much of the film takes place in adverse weather conditions, and I’ve read that all that wind and rain and mud and cold made for quite a gruelling shoot at times. What were some of the practical challenges for you there as a costume designer?

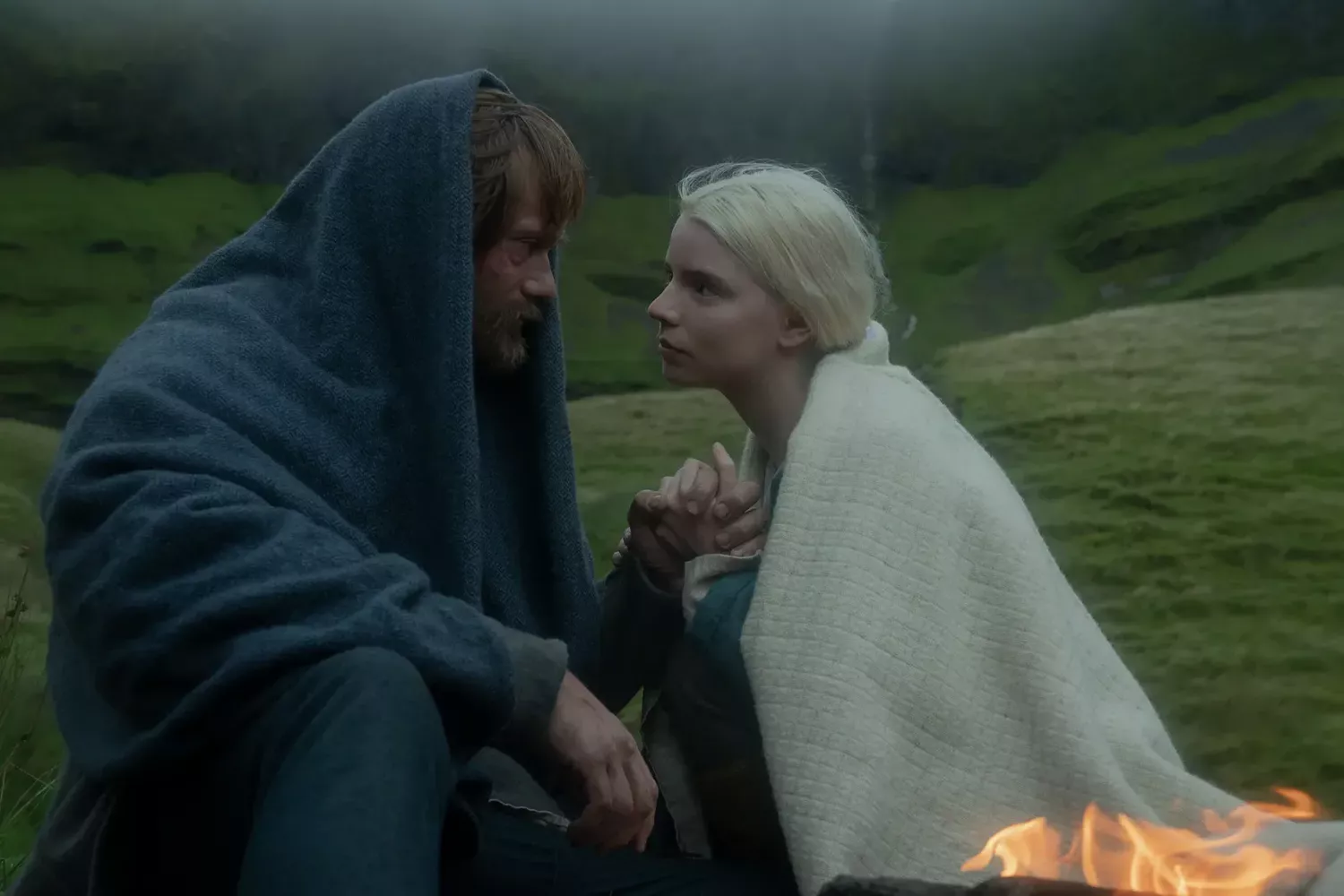

The weather aspect was really about shooting in the conditions that the script suggests, and these are the challenges that you always go through when designing things—every script always comes with practical considerations for the costuming. But here a lot of it was really about trying to keep the actors warm, which is very difficult with such long takes. They were all troopers, but especially Anya and Alexander; their costumes gave them the least protection because of the status of the characters they played. At some points, it rained every day nonstop, and even if it doesn’t read on camera, there was a drizzle most days. So over a long shoot, that’s quite challenging. We were shooting in circumstances on the mountains of Northern Ireland that were much colder and wetter than we had initially anticipated. So we created barefoot shoes that we painted and dyed to look like muddy feet to try and keep them warm. The crowd was incredible. In Northern Ireland, they have the most committed crowd performers I have ever encountered. We were blessed with not just an incredible crew but also these performers who were up for portraying such a difficult world to recreate.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Originally published in Vogue US

Oscar Novak as Young Amleth, Ethan Hawke as King Aurvandil, and Nicole Kidman as Queen Gudrún. Photo: Aidan Monaghan / Courtesy of Focus Features